How "Connectivity Credits" can help a billion young people get online

Chris Fabian, Co-Lead, Giga, UNICEF

Bill Tai, Founder, ACTAI Global

Aya Miyaguchi, Executive Director, Ethereum Foundation

Andile Ngcaba, Chairman & Founding Partner, Convergence Partners

Alex Wong, Chief, Special Initiatives and Co-Lead, Giga, ITU

- 2.6 billion people aren’t connected to the internet today

- Giga, the UNICEF & ITU partnership to connect every school in the world, endorsed by the Secretary-General in his Roadmap for Digital Cooperation estimates that it will cost upwards of $428B to build the infrastructure necessary to have a fair, inclusive digital humanity.

- Giga can explore the creation of a new product to align industry, investors, and governments in connecting every school: a ‘Connectivity Credit’*.

- A Connectivity Credit could, like a carbon credit, be an incentive for those seeking to provide connectivity to less profitable areas by building up a marketplace where ‘connectivity’ can be traded across providers, users, and geographies.

- Advances in blockchain technology, cryptocurrency, and digital finance, can make the issuance of these credits, the real-time tracking of them, and their fungibility relatively low friction, particularly compared to a legacy setup like the carbon market.

A “Connectivity Credit” would be a fungible, tradable, liquid “token” representing connectivity. This “tokenized Gigabyte” would be used to track connectivity efforts for marginalized populations, to provide incentives to technology companies creating connectivity opportunities, and to create a global marketplace where any actor could be part of the effort to provide universal, safe, and useful connectivity.

As we have seen during Covid, when people are not connected to the internet their ability to learn, work, and create is significantly diminished. Giga combines UNICEF’s focus on children and education with ITU’s experience in connectivity policy, to ensure that every school in the world has access to the internet – and every young person has access to information, opportunity, and choice.

In addition to connecting the more than 1 billion young people that Giga is aiming to serve through their schools, last mile infrastructure (including everything from ‘where the fibre ends’ – all the way to wireless access points and digital hubs in communities located on schools) can also be used to allow for other public (and private) growth of internet access. A key issue in rural connectivity discussions revolves around population density and revenue per user. Using schools as a ‘hub’ for connectivity allows Giga to create cashflow guarantees and other levers to strengthen investment cases at a national level.

However, many of the poorest areas are also the most difficult to connect. It has been difficult to prove the business cases, as there is not, usually, pre-existing revenue from the poorest communities that can be used to estimate future profits. Additionally, these communities often don’t have other fundamental infrastructure like electricity or roads making it even more expensive, per unit (per school) to connect.

A Connectivity Credit would create incentives for service providers and other technology companies to extend networks to the poorest regions and connect public facilities.

It would provide a way for governments to account for and manage multiple different lines of public expenses, and It would allow for the most disconnected areas in the world to count and credit when they are connected. The Giga project, with a focus on school connectivity and real-time monitoring is a perfect example and initial use-case for a Connectivity Credit.

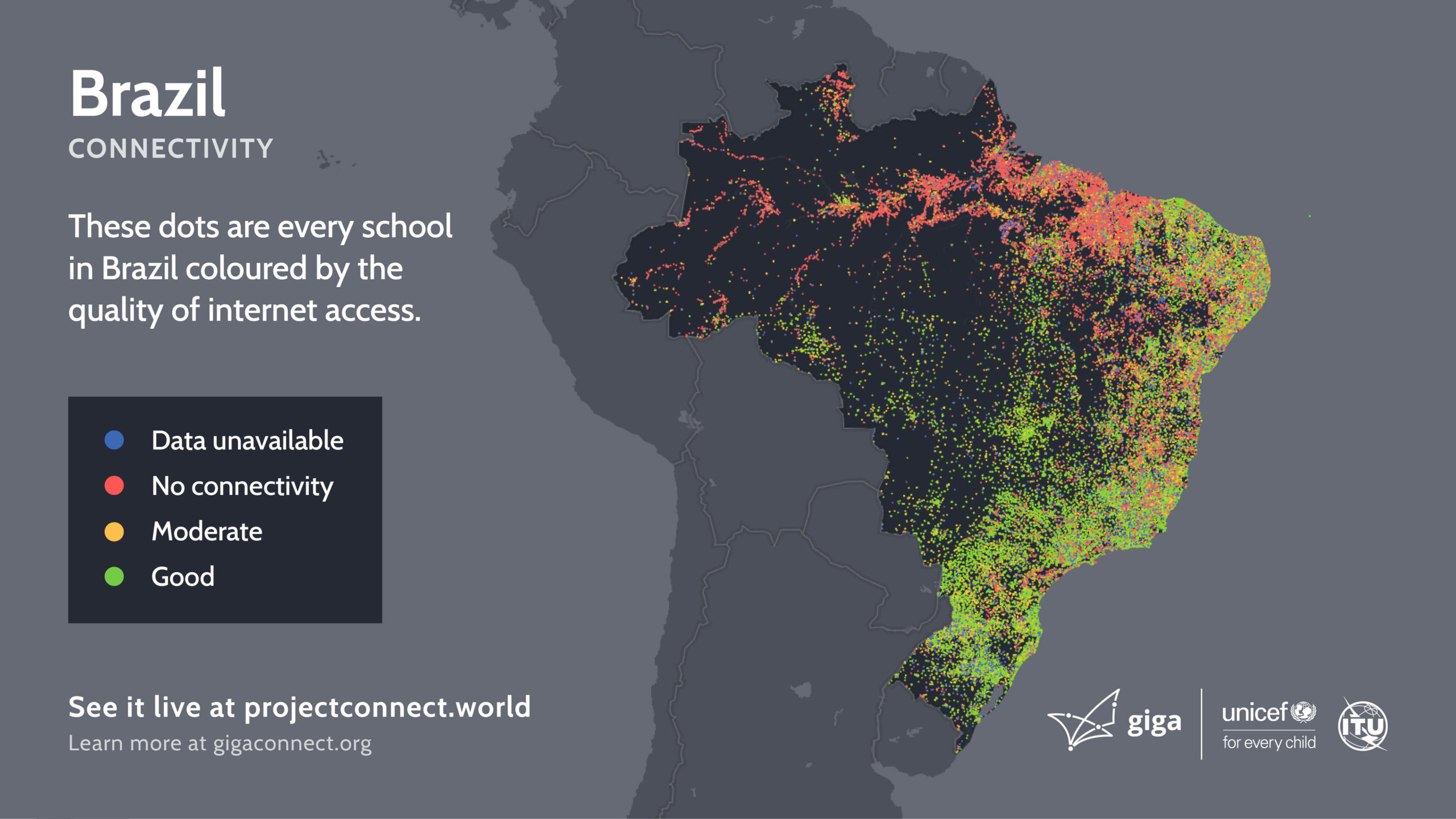

Projects like Giga give us, for the first time, a denominator of human need for connectivity. This information can help peg the Credit supply. Currently, one knows the number of schools in the world. Giga has mapped 1,000,000 in the last 18 months. In the next 36 months Giga will have live data about somewhere between 6 and 9 million schools.

As the number of connected schools increases, the Credit supply could decrease, making them more valuable over time. The Credit could then represent yearly cost and an provide an ability to see delivery of gigabyte to each school.

Connectivity Credits could be backed by a basket of currencies (fiat and crypto) from sponsor nations and partners. Increased global connectivity creates more users online, more opportunities for digital commerce and enterprise, and more space for innovation in new markets.

This backing could come from entities who have an interest in increased global connectivity as a “layer” for their own enterprises (whether those are development- or business-oriented). It can also be drawn from national Universal Service Funds or similar mechanisms which already are ‘taxing’ connectivity but are often underutilized.

Schools, to begin with, and then later other public facilities, could be issued a certain number of credits with more credits being issued depending on the condition of the school.

Projects like Giga, working with Ministries of Telecommunication and Finance, can provide assessments of the difficult of connecting any given school based on factors like distance from existing infrastructure, or difficulty of terrain. Eventually, Credits might allow schools to access software or services online, or to incentivize the creation of open-source digital public goods, through a variety of partners interested in supporting this new 3.5 billion person market.*

*Groups like Gitcoin are already launching systems to ‘tokenize’ public effort in creating open-source public goods.

Because Giga monitors school connectivity in real-time, the actual efficacy and distribution of gigabytes can be counted.

Unlike carbon sequestration, where a provider needs to sequester a minimum of one metric ton for a tCO2e credit, units of connectivity can be measured in granular detail (to the kilobytes per second). Additionally, connectivity monitoring is built into the network itself. Once a facility is connected it is already reporting on its connectivity status through the medium of connection.

Schools would be granted Credits (based on the difficulty and cost to connect them). Giga, with partner Ministries, could help assess utilization and functionality of connection.

Network Operators, ISPs, and other connectivity partners would collect Credits as they provide connectivity. Hosting providers and other digital public good partners could participate either in the primary or secondary market.

Governments already tax internet service providers and mobile network operators. Governments also provide the spectrum licenses to these providers to operate. This bi-directional flow of incentives, including potential tax-breaks, subsidies, other guarantees, spectrum allocation and more, and links to other ESG areas like renewable energy credits, makes government an ideal partner for using credits at a national level.

The global market could access the backing, or reserve, described above to issue more credits for certain areas, or could raise more money and increase the size of the reserve, should it need.

An interesting thought experiment would be to imagine a scenario where wealthy governments agree to lowering tax burdens on multinational companies which are providing Credits from work done globally, effectively allowing for onshoring of profit and other incentives.

One of the many lessons from the world of carbon credits is that building an alliance, and a global, unified standard from the beginning will help drive adoption and create liquidity. If this is done, a Connectivity Credit framework could create a global marketplace of connectivity for the most difficult to reach populations. It could incentivize “good behavior”: connecting difficult-to-connect schools and communities. It could be created when public infrastructure is built in underserved areas, allowing for service providers and others to redeem these Credits for tax breaks or other incentives.

If you’re interested in learning more, tweet us @gigaglobal and @chrisfabian

Thank you to Uwe Steckhan, Anastasia Nedayvoda and Yu-Ping Chan for their close reading and thinking through elements of this piece.

Credit to Christina Lomazzo, Mehran Hydary, Alex Sherbuck, Naroa Zurutuza and the rest of the UNICEF Innovation and Giga team as well for their inputs into this project.